When he named his series of photographs Nude visiting an exhibition or Nude visiting the studio, Robert Schwarz deliberately decided to drive the spectator on a wrong track. By doing so, he prepared the ground to lead us to an inescapable parallel with the Nude descending a staircase, 1912, which resulted into the well-known historical scandal. Admittedly, Duchamp's masterpiece conjures up photography and, more particularly, the motion-analysis as developed by Marey, superimposing on a canvas the successive states of a cubified woman in movement. But this is a wrong track, just a gesture of pretended decency to divert the too-superficial observers, who will just smile and go their ways.

There is much more, in these series. And in a very different register: that of a profound questioning of the respective statuses of painting, of photography, of the museum as an institution, of the artist's studio and, finally, of the artist and of the spectator of his artefacts.

Let us then observe.

In a first series, Nude visiting an exhibition, Schwarz proposes us images of a naked young woman strolling in the galleries of Vienna's Leopold-Museum, staring at paintings of artists of the Wiener Secession, or trying to imitate the posture of the nude female models depicted on these. When analysing the artist's proposition, we thus have, from the inside to outside, from the past to the present:

1. A naked woman, probably a model from the beginning of the 20th century;

2. A canvas painted by Schiele, Makart, Klimt or Kokoschka, dating from the first quarter of the 20th century and duly collected in a museum during the second half of this same century, recording the image of this naked model for a quasi-eternity;

3. A naked young woman, a model of our time, four or five years ago, in the galleries of the museum, imitating the posture of the painted model or observing it;

4. A photographer — Robert Schwarz — recording, on the same day, and also for a quasi-eternity, on a film, the model looking at or imitating the other models depicted by Schiele or by one of his contemporaries;

5. A spectator-observer — you or me — today, tomorrow or later, looking at a print of the preceding film.

6. One could also imagine another spectator, looking at this same photography, reproduced in a catalogue or on the page of an Internet site.

What a mise en abyme! What a reflection over the flow of time, with its six nested levels of reading!

In the second series, bearing the same title, created for an exhibition in Limoges, in 2002, the process is the same one, the only difference being an even deeper perspective. The naked young woman does not stare any more at a canvas of an illustrious and museum-exhibited painter, but at a series of reproductions, of pastiches purposely created from celebrated historical paintings of nudes. Between steps 2 and 3 of the previous process, one can thus insert the two following ones:

2.1. A painter — Schwarz himself? — some time before the exhibition, creating copies of several celebrated paintings of nudes, under the form of small canvases;

2.2. Technicians hanging the small canvases to create a kind of mosaic in the L-shaped corner of two walls, a short time before event 3.

We now have eight nested levels of reading!

The third series, Nude visiting the studio, presents another nude model, standing in front of enlarged photographs of works of the preceding series, hung as a mosaic on the walls of Schwarz's Parisian studio. The mise en abyme continues, with three new steps between 4 and 5:

4.1. Robert Schwarz, between 2002 and 2006, covers the walls of his studio with prints of the preceding photographs;

4.2. A model, different from the one on the preceding photographs, Esa Bang, stands, in 2006, in front of the walls of the studio;

4.3. The photographer records the scene for a quasi-eternity.

Eleven nested levels of reading, now!

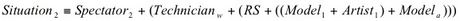

If I ventured myself to transcribe into sets of equations — with a self-explanatory notation — the steps of the first series of photographs, I would write:

1. Model1

2. Model1 + Artist1 → Picture1

3. Picture + Modela → Situation1

4. RS + Situation1 → Photography1

5. Spectator1 + Photography1 → Situation2

6. Spectator2 + (Technicianw + Photography1) → Situation2

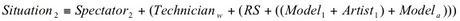

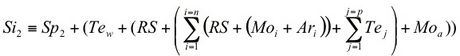

Condensing the above into the following equation:

or, under an abbreviated form:

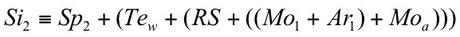

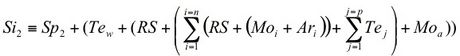

Using a similar notation, the second series could be expressed as:

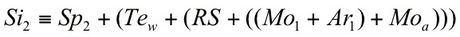

And the third one as:

Robert Schwarz thus confronts, within the same work, several levels of temporality converging towards the same object, the nude, not considered as an end per se, but as means, as a vector of a mise en abyme, as an ontological questioning. No indecency, therefore — Diderot indeed wrote: indecency is not the nude, but the tucked-up —, but some shamelessness, a liberating shamelessness, as Schwarz declares: the complexes related to the body are supported by the sense of shame, which is a reactionary value that exerts on our lives a permanent repression.

The nude, a colloquial subject of the academic painting since the classical age, has almost disappeared from the artists' production, since the Futurists' asserted a moratorium: we require, for ten years, the total suppression of the nude in painting. Schwarz reintroduces it, but dissociates himself from the traditional pictorial practice, thus echoing Brassaï's words: photography is the very conscience of painting; it unceasingly points out what it should not do; let painting thus take its responsibilities. Picasso answered him, as an echo, in one of his letters: photography came at the right moment to liberate painting from literature, from anecdote, and even from the subject.

Schwarz, as an artist, takes his responsibilities and assumes them... And these responsibilities go through transgression, through numerous transgressions. A nude in a museum is not, by nature, of a transgressive type, since generations of self-righteous bourgeois regularly strolled in, with their spouse and their offspring, to visit the galleries, the temporary exhibitions or the treasures of the permanent collections. Naked flesh obligingly offered to the eyes of the spectator then outnumbered the evocations of battles, the portraits of celebrities, the figurations of religious episodes and various still-lives.

What is transgressive, with Schwarz, is not to have the nude step out of the canvas — sculptors already did it —, but to strip the voyeur bourgeois and to put him face-to-face with his phantasms... Worse still, to turn this embarrassing and compromising situation into a work art, into an object of observation or of voyeurism for other spectators... The visitor, thus instrumented by this young naked woman, becomes, by delegation or by transfer, the one by which scandal happens, materializing, in a remarkably unambiguous manner, what must be not seen, what must not be revealed, what must hypocritically remain within the skull, under the feather blanket or between the four walls of a brothel.

Admittedly, would one object, nudity was a current matter in the artists' studios, as of the 18th century. It also fed the phantasms of a certain intelligentsia. There are even photographs depicting student painters posing, circling around their Master, in front of one or more naked models. And this was no matter for scandal... Scandal comes, with Schwarz, when the naked model in the studio turns into a full-pledged work of art. There is however Courbet's L'Atelier (The Studio)... Indeed, but this work behaves as an allegory — a real allegory, Courbet said — and as a political proclamation — for the Irish cause, in particular —. Also, as a matter of fact, the naked model is covering her breasts with a sheet, which did not prevent the scandal...

In Fragonard's Les débuts du modèle (The Model's Beginnings), belonging to the collections of Musée Jacquemart-André, an elderly pimp presents the artist with a bare-breasted young model. The painter, armed with a cane, tries to tuck up the skirts of the girl in order to unveil her intimacy, attempting by this sole gesture, to reduce the future model to the status of a mere object. This painting dates from 1765-1772. Here, as Diderot would say, one is in the area of the tucked-up, in the register of indecency, not in the one of shamelessness.

The essential difference probably lies in the fact that Schwarz's models, though real and almost palpable, do not stand for anything else than for their own nudity. Their bodies, vulnerable and often slender, do not tell a story, do not want to make us dream nor fantasise. They are like the hieroglyphs of a new writing, like mediators between a signifier and a signified, transposing, into plastic terms, the four levels of the expression that saint Augustine develops in his De Dialectica: verbum (word) — dicibile (effable) — dictio (proposition) — res (object).

In his own way, through multiple variations on an obsessional theme, Schwarz tries to exhaust all combinations of images that can be built around a nude female and its graphical representation. Like the mathematician who appeals to the rules of algebra in order to build models ad infinitum, Schwarz develops themes but does not create, everything being already contained in germ and potential in the rules that he initially set. Schwarz thus echoes Calvino's words when he declares: photography has a meaning only if it exhausts all possible images.

More generally, Schwarz questions the positioning of photography among the various forms of artistic expression. In 1935, in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin wrote: one had been wearing away in vain subtleties to decide whether photography was or was not an art, but one had not wondered whether this very invention did not transform the general character of art. More than seventy years later, Schwarz raises the question and brings his own answer.

Louis Doucet, August 2007

Translated from the French by the author