"Great pop music is forever tied to the moment it first touches you. Some critics say this makes such music valuable only as aide-memoire. I believe it suffuses it with enormous significance; anything that helps us travel with the ever-passing moment of the present is of vital spiritual value in the chaotic world we inhabit. Living in a travelling moment we might be lucky enough to lose ourselves; that seems to me precisely what happens during orgasm." 1

Sitting in Starbucks on Wardour Street 26:21

Paranoid Acoustic Seduction Machine by Momus 03:06

It's near impossible to resist the promise of the Pod - a shiny compactness that makes your music collection and life more manageable, more portable, more more. It puts a new face on the appeal of taking your music everywhere, anytime across the barriers of space, time and in and out of love. Plus it vows to be yours and yours alone - unlike a Walkman an iPod can't easily be shared. This is your chance to possess music as obsessively as music can possess you. The iPod acts as the medium at the hub of a digital seance inhabiting a Julia's Bureau of sorts 2 - channelling inner voices, inserted thoughts, dislocated utterances, shared playlists and transmitted codes.

Flip the iPod over and you'll find another highly seductive surface, highly polished chrome. The back of the iPod serves extremely well as a mirror, reflecting i back at the self. Engraved into the centre of the casing is the Apple logo, the post-temptation Apple, reflecting back at you in such a way that it's easy to project yourself taking that bite and in doing so opening up the third eye of the soul. Koestenbaum's assertion that the early phonograph was sold as "a kind of confessional" or as a mirror reflecting "your soul - and what is hidden deep with in it" 3 has been updated and preserved by the eyePod.

Walking from Warren Street down Tottenham Court Road 12:16

I'll Be Your Mirror by The Velvet Underground and Nico 2:10

Apple's initial fusing of an "i" onto the long-established Mac lovemark 4 appears to have derived from a desire to emphasise the relationship between your new computer and the internet. Crack open the packaging, slip the sexy translucent TV-like object onto your retro-futurist Habitat table, plug it in and - say hello to the internet. This idea of the Mac in the corner as a lifestyle accessory - or 'digital hub' - extends nicely into the iLife suite of software, iTunes to organise your music collection, iPhoto to manage and manipulate your photographs and iMovie combined with iDVD to create and output your home movies. The arrival of the iPod further extends Apple's mystical all-seeing-i.

The i takes on a whole new significance with the iPod. The seamless integration of the iPod with the iTunes music player and in turn the notional virtual jukebox of the iTunes Music Store (i.e. music purchased and downloaded via the internet) sits comfortably alongside the original connotations of course, but the iPod metaphorically capitalises the i and makes it myPod.

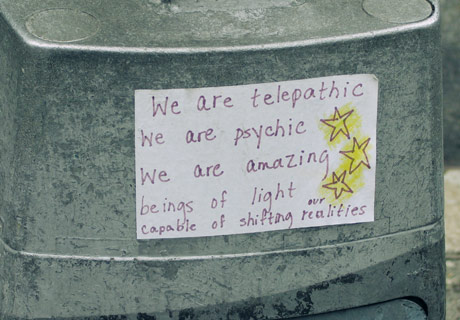

A "New York Seen" article in the Village Voice 5 describes a graffiti attack on a block-long row of iPod posters on the east side of Lafayette. An anonymous scribbler annotated each poster with his or her own definitions of the mystical i. "The 'i' stands for isolation" reads the article's lead image of a defaced billboard. The piece concludes with a rather obvious analogy between another of the graphitised strap-lines "The 'i' stands for I Want One" and the work of Barbara Kruger. Twisting the piece into a too-cool-for-school critique of consumerism sidestepped the more perceptive insight offered in many of the slogans "The 'i' stands for intimate", "...I can't stand the silence", "...individual", "...imaginary", "...I don't want to talk to you", "...inside", "...impossible", "...introvert", "...incubate" and "...id (Freud)".

MyPod's i is about much more than ownership though, it's about the I in 'self', not myPod, rather my selfPod. A programme of personal bonding has been coded deep into the projected image of Apple's seduction machine. The walls of the city are plastered with multiple monochromatic posters presenting an eccentric cast of characters frozen in a moment of personal rapture, iPod jammed firmly in their ears. Each image is an expressive stop-motion silhouette caught in the act of listening as a performance, die-cut into the vibrant Warhol-pop-palette backgrounds. These empty placeholders are ready to be filled-in by you with heightened projections from the theatre of self; each displaying exaggerated symbols of their desirable position in the cultural elite - the beads, spikes and dreadlocks on the heavily stylised fringes of counterculture.

Apple's choice of the word 'pod' is intriguing. Why not the iMusicplayer, the iJukebox perhaps? Why not the iMan as the logical digital successor to the WalkMan and the CD based DiscMan? The word Pod has a wonderfully retro-futuristic ring evoking the stylish white rounded corners of the gadget itself but it also suggests something of the time capsule and a sense of looking backwards and forwards at the same time. The iPod stores a set of memory-triggers for later retrieval much as the personal time capsule might. Further relationships can be drawn with the wider definitions of the word pod... like the fruit of a leguminous plant serves as a protective shell distinct from the seeds it contains, so too the iPod serves to encase and preserve the seeds of memory digitally held inside. The iPod stands for your independence of choice and your freedom to listen to expression. It's stands you apart and alone, it's a solo adventure into your self with the capacity to non-stop soundtrack a month long trip. A technology of the self, seeded with memories to fuel a journey re-establishing your sense of continuity with your past mapped into your present. A compact digital-update of Sailor's jacket in 'Wild At Heart'.

Sailor: "Hey! My snakeskin jacket. Thanks baby. Did I ever tell you that this here jacket represents a symbol of my individuality and my belief in personal freedom?"

Lula: "About fifty thousand times" 6

GNER Train from Kings Cross to Newcastle 3:24:47

Living Space by John Coltrane (with Alice Coltrane) 10:26

Typically, the telltale white ear-buds of the iPod are spotted on the move. The device is used to aid the passing of time when walking, jogging, flying, travelling by train - shared spaces where the promise of immersion in a private digital landscape is hard to resist. The portable digital memory-retrieval machine fuels the escape-fantasy, inspires dreams and aids the trip. Recalling the blending of actual and metaphorical trip as exemplified by the movie 'Easy Rider' the iPod accompanies the physical road trip whilst fuelling and soundtracking the submersive psychedelic trip.

This iTrip also recalls Kodwo Eschun's 7 musings on John Coltrane's encounters with Sun Ra and the Arkestra and comparison to Manuel De Landa's explanation of LSD's neurochemical processes: "When you trip you liquefy structures in your brain, linguistic structures, intentional structures. They acquire a less viscous consistency and your brain becomes a supercomputer. Information rushes into your brain, which makes you feel like you're having a revelation. But no one is revealing anything to you. It's just self-organising. It's happening by itself." The iPod interrogates the databanks of this supercomputer and retrieves digital traces, the random play button self-organising the available data recalling and inspiring new self-revelations. And it's happening by itself - those 10,000 tracks each a jumble of ones and zeroes are transmitted from the retrieval machine sent down the little white wires and directly into your brain.

Many fans of the randomise feature on the iPod believe that random isn't really random. The Internet is littered with conspiracy theories, including a long-running discussion thread at macslash.org titled "Is Random Really Random In iTunes?" 8 Theories range from hugely complex logarithms working away in the background based on beats per minute, key, time signature - or more straightforward metadata such as composer, year or genre. Of course, each of these it met with counter-claims that there's no inbuilt space-magic, just a poor algorithm say some, generating a poor version of random. It's all in the mind say others - perhaps an excellent of pattern-fulfilment - we remember the instances where the software appears to make an intelligent choice (Antony & The Johnsons slips into Nina Simone, and there must be a ghost in the machine, right?) and immediately forget the non-precognitive selections that more typically appear. Perhaps the most compelling argument against this digital spirit-guide lies exactly in that - why, then, do these same forces not render iTunes a flawless superstar-DJ? There's also the nerds, of course, who only really want to debate whether it's possible to programme true randomness, the amount of processing power that would be needed to generate random numbers and the use of PRNG's (Pseudo Random Number Generators) in cryptography meaning that 'good enough' algorithms exist that, if used with a good enough seed 9 , would make iTunes appear more random.

Seeded in our iPod portable memory-retrieval device are thousands of tracks and each of their compositions has a schematic form of musical patterns, such as down beats, drum patterns, chord progressions and motifs common in music of its genre. As music is easily understood in these chunks and also in refrains, whole songs and sequence of songs it can be learned and stored efficiently in long-term memory. Multiple listens build up a sequenced, structured representation of tracks and playlists in our memory. This leads to a semi-conscious expectation, and often urge, to hear one song after another if we're used to hearing it within the sequence of an album or its position on a compilation. Before we hear, or even consciously acknowledge what we're expecting to hear semi-activated memories enter the peripheral consciousness as a feeling of what is about to happen. The random function on the iPod constantly disrupts and disappoints this sense of expectation momentarily surfacing a feeling of disjuncture. These attempts to sabotage the links forged in our nervous system between recognition and expectation by dislocating recollection and anticipation result in an unsettling intensifying of the local order of the present.

As the iPod keys directly into our episodic memory, on hearing the first few notes of a tune a partial autobiographical memory can be triggered, this memory is copied when recollected and the copy replaces the original memory. This makes these memories vulnerable to various kinds of transformation and distortions; they become disrupted by digital-static. This is amplified through interaction with 'semantic memory' - the long-term memory for abstract categories not concerned with emotion. This process of abstraction collides with the pseudo-random provoking of episodic memories as they're loaded in and out of the RAM in the brain's supercomputer. Through this copying and re-copying are our autobiographical memories liquefied? And does this free the mind from real-time reality and real-time remembering, digitally fulfilling the quest for freedom ultimately denied to Billy and Wyatt in 'Easy Rider'? If you're willing to pursue the 'trip' then random presents the chance to have your digital-spirit-guide score a period of your life - so a 60 minute journey across London could be re-mapped in potentially endless configurations of a random selection of any sequence of about 18 songs from a possible 10,000 tracks each with the power to trigger a shifting set of associative connections.

Walk from London Bridge Station to Tate Modern 23:57

The Sinking of The Titanic 24:25

The liner notes for Gavin Bryars ''Sinking of the Titanic' 10 includes the passage "After the development of wireless telegraphy, Marconi had suggested that sounds once generated never die, and hence music, once played simply gets fainter."

Bryars' epic composition is a sonic spectre, summoned through layering rumoured and reported actual 'hearings', hymns played as the ship went down and the band played on. The score is arranged to ebb, flow and dissipate to a scientific trajectory of the sound-journey. The piece evokes a sense of oceanic space above, around and below. It's a siren call to our experience a non-grounded state of mind, to drift away on sonic waves.

Romain Rolland coined the term 'oceanic' in a letter to Freud. In counter-arguing Freud's attack on religion, Rolland explained the true source of religious sentiments to be "a sensation of 'eternity', a feeling as of something limitless, unbounded - as it were, 'oceanic'". 11 The ocean analogy is repurposed by Simon Reynolds, who coins the term 'oceanic rock' 12 to describe music yearning for a gentle apocalypse (and end of history and an end of geography), a music desperate to liberate itself from the real world and escape into the expanses, be they the sky, the sea or the desert. Hypnotic and narcotic music, typified through much of the eighties by the 4AD label and visualised through the oceanic graphic-gaze of Vaughn Oliver and Chris Bigg at V23.

David Toop suggests that we return to the sea "for a diagnosis of our current condition. Submersion into deep and mysterious pools represents an intensely romantic desire for dispersion into nature, the unconscious, the womb, the chaotic stuff of which life is made." 13 The very idea of sea is caught up in ideas of escape, imagery of death, of Ascension, of being engulfed and then released, of the final call of the boatman, Charon, before setting sail for Hades.

Is this draw to the vast expanse of all-dimensional space and inner space connected to our embrace of the idea of an infinitely dimensional internet and perhaps, increasingly, the innards of our iPod? We have expanded our minds to accept this as a model of magnitudinous, non-linear, iDimensional and oceanic structure. A structure of potential, not form, inflating our capacity to process a perceptual space for an imaginary web: a web that offers endless possibilities to navigate a trip, endless links, connections and adventures.

Everything we hear just gets fainter until we salvage and refloat the signal.

Overground train from Clapham Junction to New Cross Gate 32:57

Slow by My Bloody Valentine 04:20

In 1923 Johannes Greber, a Catholic Priest, became interested in communicating with spirits. By 1937 he had produced a new translation of the Bible correcting the errors of earlier translations through personal revelations he believed were received from the spirit world. In 1932 he published "Communication with The Spirit World Of God Its Laws and Purpose".

"Mediums are intermediaries or human instruments employed by the spirit-world to make itself manifest to man... At times the medium's body itself is transported from one place to another, occasionally over great distances. This is also done by de-materializing it at one spot and re-converting it into substance at the other."

The iPod appears to possess a similar ability - a medium to use our state of mind, being and sense of time as an instrument inhabited by voodoo-like force in order to bridge the 'here' and the 'there'. But is the device the vessel that facilitates the journey or the medium through which the journey takes place? At any given time, our psyche's location depends on a balance of substance - whichever rush of information tips the balance has the power to over-run the other.

Sitting on a train, ear-plugged into the device, with your eyes closed, a single piece of music can burn away the afterimage of bored commuters swinging from the handrails and overlay it with a stream of other-consciousness. My Bloody Valentine's 'Slow', for example, is described by Garry Mulholland as a record that "actually slows down time" 14 It also floods the mind with sensations of another space and time, a village fete, childhood memories, a seaside pier, gists, concepts, automatons, seemingly random images half-recalled from a movie, imagined performances, all float in and out of the mind, and in doing so derail the conscious analytical mind. You have a less immediate awareness of your actual location because the substance of the trip unfolding in your imagination is more potent. If the conditions are right and reality not too intrusive this trip can transcend in to a trance, which, in turn, can sink into a sleep; at least until something nudges your consciousness back to acknowledging your real location.

John Lilly, a scientist exploring the properties of LSD began his research by simply injecting himself with the drug and taping the sound - field-recordings brought back from his trips. In a later experiment involving sensory deprivation and a seawater floatation tank, he reported a total change in his sense of reality: "I sat in the space without a body but with all of myself there, centred. I felt fantastically exhilarated with a great sense of awe and wonder". 15

On your trip you're slipping fluidly through reference points in space and time, but your body is still sat on the train. Is this an out-of-body experience enabled by the portable memory-retrieval machine? Or does the iPod have the capacity to become a time-travel-capsule simultaneously remapping the present and the past?

This slippage between time-states seems to flow most fluidly in the physical in-between no-places - on the train, the tube, the airport. The iPod vessel carries us through the netherworld of mental-limbo. Our understanding of duration (time-passing) in music, through its time frame, beats and phases keeps time with our understanding of the duration (passing time) on our journey through markers of progression, station stops and different phases of movement.

This sense that we can be here and there, here and not here, here and somewhere else or perhaps in an advanced state, here and everywhere calls up Heidegger's terms 'Da-sein' and 'Befindlichkeit' as possible existential expressions of this state of there-being and a where-you're-at-ness....the

Waiting for Sparks to play at the Royal Festival Hall 27:02

Ecstasy Symphony / Transparent Radiation (Flashback) by Spacemen 3 09:51

The human understanding of acoustic space is dependent on not only the scientific principles of acoustics but also on how we sense sound and how we feel sound. Our physiological make-up means that we do, physically, feel sound via the vibrations transmitted through the body. We also sense sound, through a learnt understanding of how objects exist in space, motion, gravity, speed, distance. We can sense that a bird flapping its wings overhead is generating a very different sound to the motorbike engine revving next to us without needing to actually hear either. Evolution and our environment have also determined our spatial perception.

Music is usually recorded in an environment very different to the environments it will be heard in. The recording studio or the concert hall have huge sonic variations from the bedrooms, vehicles, offices, bars and outdoor landscapes the recorded work is more likely to finally be listened to in. The role of the engineer in the recording studio is to create a sound recording that will remain effective when relocated. The most common tools of this trade are digital delay and digital reverb. Once the extraneous sounds of the studio and the sound-carrier (such as tape-hiss) have been removed, these two pieces of studio trickery are combined to create the sound of space. Location, perspective and dimension are reconstructed in a void, a phantom space that doesn't exist, an acoustic-limbo. This nether-space is our space, mapping out our soundspace - the sound of the listener.

The telephone as a sonic-transmission device denies much of our ability to sense the soundspace of the transmitter, the disembodied voice. Delay, distortion and static on the line weaken the signal and there's a mind-slip preventing us from understanding if the other speaker is near or far, broadcasting from this side or the other side.

Walking from Redux 116 Commercial Street to Aldgate East Station 14:53

Eric's Trip by Sonic Youth 03:48

Your inner speech is your own. Music, at its most harmonious, can help us make sense of our inner experience, share a language with our inner voice and suggest a structure and coherence to our emotions. However, in dislodging these moments of music from where we expect to find them and when we expect to hear them and relocating them in unexpected environments we set up heightened conditions for traces of schizophrenic activity. The iPod is semi-resistant to fragments of schizophrenia as it serves to help us to sense personal continuity through time and acknowledge a real-time structure for the passing of time in reality. When we're focussed on the present the iPod sits in the background acting as a regulator, a kind of (mind) control for remoteness - a fix of sorts. It reduces the likelihood of prolonged exposure to silence and becomes an avoidance machine diverting our need to endure solitude or make sense of the ambulation of our own thoughts and mind.

"There's something moving

Over to the right

Like nothing I've ever seen...

I can't see anything at all"

Sonic Youth 'Eric's Trip' 16

Studies of the disordered mind report that many people, especially those with schizophrenic tendencies, experience their inner speech as the voice of another person. They hear voices in their head that they don't recognise as, nor believe to be, their own. Hearing alien voices or inserted thoughts is like finding that you lapsed into a daydream or fantasy without meaning to, or without even really noticing when your thoughts slipped into another plane. Your subconscious has come out to play.

What happens when the voices fed into your head channelled through the wires from our portable memory retrieval machine talk over our inner voice or transmit in a different tone? If the vocalist unexpectedly addresses you directly, could his or her voice in your head be experienced as an interruption to your real-time thinking? Could this alien voice speaking inside our head be perceived as inserting a thought? If this dismembered voice taking up residence in your head, talking in place of your inner voice begins to induce traces of schizophrenic activity does it tip the balance in our minds to an alternate reality trip, temporarily dislocating us from the here and now? This may lead to experiencing a hypnotic oscillation between background and foreground, the here and the there. Are we tripping towards a disruptured sense of human self-experience and an alienated self-consciousness?

As we surrender to the temptations of an immersive experience escaping reality and a sequence of lyrics, sounds or songs trigger a trip through an ever-unfolding hybrid hallucination part-narrative, part-action-collage many of the ambulations of our mind fuelled by the music may be experienced as coming from elsewhere; episodes in our mental activity, our mind's eye that we don't recognise. This reads like a philosophical recipe for inducing what on the one hand could be a psychedelic experience and the hand's of someone else a schizophrenic manifestation of alienated self-consciousness.

Stephens and Graham in their philosophical investigation 'When Self-Conciousness Breaks' 17 attribute episodes of alienated self-consciousness to the subject's disturbed sense of agency; a condition in which the subject no longer has the sense of being the agent who thinks or transmits the thought. Maintaining the balance relies on our ability to distinguish the sense of subjectivity from that of agency. For example a voice fed into our head via the telephone is unlikely to feel like an inserted thought - the disembodied voice amplified down a disembodied plastic limb may well spark uneasiness, but it seems the agency of transmission remains separate, exterior, distinguishable and in the fore. The eyePod and its discrete line into your mind is a less apparent as a form, less distinguishable, lurking in the background - a smooth operator, an agent secreting itself into our sense of subjectivity.

Waiting for friends on the Duke of York steps, The Mall 10:11

Frenz by The Fall 05:22

Listening to music on your home hi-fi or on a desktop computer you retain control over the micro-journey. Tracks can be skipped, discs shuffled, even randomising features of desktop-based software media players make intervention simple - if a track pops up you don't want to hear, skip it, if you see a track coming up in the playlist and you'd rather it didn't, just delete it - it's pseudo-pseudorandom. But listening to an iPod, there's always the possibility that interfering with the transmission will not be possible.

Many iPod owners now tend to discard the tell-tale white headphones, fearing their potential to be read as a "please mug me" sign. Paranoia has driven the white ear-buds of the city-dwelling iPoddite underground. The same fear renders a give-away flash of the remote or a quick fumble with the Pod itself out of the question. Random is as random does. Coupled with the physical personal-safety paranoia, is the psychic paranoia of knowing that encased in the portable memory-retrieval machine is the possibility of transmitting a bad iTrip. The wrong-song-at-the-wrong-time-fear, the inappropriate-soundscape-for-the-current-reality-dread, or the shit-did-I-really-forget-to-delete-that-Kylie-track paranoia when the private leaks into the public.

When file-sharing first began to appear on US college campuses the more technically savvy students realised they could use the Local Area Network provided by the institution to share music between their dormitories. Campuses were being turned into shared-memory-retrieval devices - the vast digital jukebox in the sky long-since prophesised by the mavens of new media. The downside of being able to tap into the music collections of your fellow students, of course, is that they can also tap into yours. Upshot: A campus-wide purging and purification of digital music collections. An illegally downloaded collection of Christina Aguillara tracks might be fine for your personal, private indulgence - but is less desirable when the rest of your school knows the Dirty secret soiling your otherwise immaculate playlist-portrait.

What happens on your iTrip when your soundscapes clash? When the cool kid you've caught the (bright) eyes of on the tube suddenly realises that you've got Bonnie Tyler leaking from your headphones? And what happens when it's just a bad iTrip, regardless of the musicological merits of the track? A moment of blissed-out drifting shattered by the brutal beats of Front 242? And what of the paranoia that follows when the sounds of the here-now city are jammed from your ears by the digital roar emanating from the paranoia-pod? Like the best and worst chemical-induced trips, the internal and external collide and contradict, synchronise and heighten, twisting and distorting the experiences of the pushme-pullmePod. It's just a ride. 18

On the bus from Clapham junction to Alma Road, Wandsworth 5:12

I don't need love I've got my band by The Radio Dept. 03:15

In April 1930, a magazine began publication titled "The Direct Voice: A Magazine Devoted to the Direct Voice and Other Phases of Psychic Phenomena". In his history of ventriloquism 19 , Steven Connor quotes from a contribution to first issue by a direct voice medium, Maina L. Tafe:

"You may have a wonderful radio set and by turning to any given number on the dial, you are able to 'tune in' and listen to almost anything that is being broadcast, BUT if your radio is out of good working order, or if there is too much static on the air, what you hear is disconnected and most of the time you hear imperfectly. Now that is just exactly the same operation of the psychic machinery through which the messages of our loved ones come."

She goes on to urge readers to 'Be your own psychic radio station' or to think of the 'psychic line of communication' as a telephone call. The directness of the voice in this new and developing area of spiritualism certainly served to render many of the channels popular in earlier decades redundant. The spirit guides who would lead a medium though the ether of the other side are rendered strangely redundant in parallel with the technical advancements in sound recording, storage, retrieval and transmission. And somewhere in the spirit realm a hoard of Red Indians gather daily to bemoan their unexpected retirement.

The more physical forms of spirit manifestation relied so heavily on these psychic gatekeepers that it's not really surprising that the direct voice seance rose to dominate over the mediums still performing materialisations. It's inevitable that having an Indian Swami pass on a message from your dear departed relative is less compelling than hearing their voice, speaking in the same room as you. In fact, the Direct Voice went so far as to declare the mental phenomena of the dismembered voice as the most compelling evidence for psychical communication, admitting that other mediumistic techniques such as automatic writing and clairvoyance were prone to being tainted by the character of the medium through which the message was channelled. Perhaps this was the defence Arthur Conan Doyle offered Harry Houdini when he rejected the spirit writing generated by Conan Doyle's wife purporting to be from his dear departed mother?

The analogy of 'psychic machinery' and broadcast machinery (i.e. the radio) is exciting because it introduces the idea of static, the possibilities of distortion and the need to 'tune in'. Later spiritualist developments would see the technologies themselves becoming the vessels through which psychic communication is channelled - indeed, the technoseance channels its otherworldly communications through electricity itself, via the microphone, the tape recorder and the radio.

Sitting in Matador Records office on Broadway, NY 21:00

Everything Must Converge by Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds 03:18

The ringing of the telephone signals a call from the other side. A trumpet call. A vessel containing binary data, 1's and 0's that are the fragments that reconfigure to produce memories, a journey by boat. The boatman's call through the river cloaked in an eerie fog. The distant sound of a small, tarnished brass bell blowing in an unseen wind signing his presence. Hades, the Unseen god of the underworld is heard trough a seance performed in the dark. Death and Speed. Dislocated voices, heard but not seen. The amputated self. The dismembered voice re-membered. Seeds of half-remembered memories. Phantoms, conjured up by the ghostly reminders of the past through the not-now digitalseance. Noise and Silence. The telephone book offers tracings of the genealogy of the telephone, originating in the loss of family. Dredging memories from the ocean-trapped sounds of the Titanic, Myth and Reality. The Arkestra plays on. Nearer my God to Thee, Watson, the name of an electrically transmitted voice, the open switchboard, ready to receive through the head-phone. Purity and Corruption. Konstantin Raudive's tape recorder runs in silence, catching the voices of the dead. Vibrational bliss. Digital hiss.

Tube from Canada Water to New Cross Gate 06:58

I Feel Good by Epic Soundtracks 03:03

Out in the city with headphones on and music playing you're not just listening to a performance; listening itself becomes a performance. As Simon Frith asserts "As listeners we perform the music for ourselves."20 The music playing inside your head may begin to affect the way you act - maybe you slow down a journey to work to walk in time to a Bob Dylan beat, or you stand waiting for the tube tapping your foot along to Johnny Cash. In doing so, you conform to one of the repertory of 'I'm listening to music' physical actions... mini performances, each an enactment of emotion in a kind of mime.

In Erving Goffman's words - "All the world is not, or course, a stage, but the crucial ways in which it isn't are not easy to specify". 21 The contemporary proliferation of personal music players (the retro-cool cassette Walkman, MiniDisc, portable CD players and digital jukeboxes such as the iPod) has made these 'crucial ways' much harder to pinpoint. On our trips into public spaces, listening to the music being fed directly into our earphones, many of us begin to enact, imagine or choreograph a performance - a performance without action or movement.

The music itself is speaking directly to us, and the conversant references trigger memories and nostalgic feelings - not always personal, actual or autobiographical - but filmic. The television of western culture has provided our imaginations with a wealth of stylistic strategies ready to be summoned, imagined sequences of events to be superimposed on top of the reality around you. There's a playground of cinematic and televisual codes available to be channelled into a visual articulation of the soundtrack while we trip-out on reality for a short time. Our subconscious recalls fragments from anywhere it can and composites the samples styles and gists stirred up by the soundtrack, and the language of the omnipresent pop video providing one of the most common ways for younger generations to organise the mind's view of music performance.

With a soundtrack hot-wired to our mind we begin to composite on-the-fly memory-possibilities that are no longer our own. Most don't even seem consciously fuelled and some seem to be a semi-conscious strategy to warp reality, to make it more pleasurable. These virtual performances aren't imagineered to any specific formula, although patterns of repetition can occur when certain scenarios fit over multiple soundscapes and consistently produce a sustained pleasurable effect. When the percieved synchronicity of small events occur then they can feel imbued with extra significance -as though possessed by phantom, revelatory links between what happens in your head and what happens in the world. This prompts a lucid response... a kind of vivid daydream.

In her essay 'To Destroy The Sign' 22 Vera Dika writes: "By the late 1990s the understanding that media images dominated our lives had become a commonplace notion. A general feeling of being 'trapped in a movie', or of what Baudrillard had called the loss of the real, was often expressed in cultural works.". Dika's critique is of a recent filmic trend to present a fabricated 'real' - exemplified in The Truman Show and Pleasantville and their commentary on the incursion of images and simulation into our daily lives.

The interest we now share with the media in using fantasy sequences illustrates a different relationship with reality, and a fear of being trapped in the replica. The time-spaces in reality that coincide with our predominant use of the portable memory retrieval machine are the dull bits, the in-between states filling time from A to B. These slices of reality trap us, and we call on this device and the effects it can have on our mind. The present becomes an indexical mark and we can escape from its repetition when we choose to. In this move we're also using a device to rupture the surfaces and cognitive processes of a real world now temporarily anterior while spatially still present. We're acting and re-enacting at the same time - the present tense is a double exposure.

Virgin train from Euston to Liverpool 03:02:02

4"33 by John Cage 04:33

1926. German playwright and author Bertolt Brecht writes "The Radio as an Apparatus of Communication". He notes:

"Radio is one sided when it should be two. It is purely an apparatus for distribution, for mere sharing out. So here is a positive suggestion: change this apparatus over from distribution to communication. The radio would be the finest possible communication apparatus in public life, a vast network of pipes. That is to say, it would be if it knew how to receive as well as transmit, how to let the listener speak as well as hear, how to bring him into a relationship instead of isolating him. On this principle the radio should step out of the supply business and organise its listeners as suppliers."

Following the launch of the iMac Griffin Technology, a Nashville based company specialising in products for the Mac market, quickly appended Apple's all-seeing-i onto their product lines. A universal ADB to USB adaptor becomes the iMate and a USB audio interface the iMic. An enormously popular add-on to the iPod is the iTalk. When it was first launched it was the wet dream Mac-fantasists had been waiting for - a small microphone that can be attached to the top of the pod finally rendering the eyePod wide-open to receive.

The portable memory-retrieval device is also, of course, a vessel for transmitting digital soundscapes, and Griffin's recently launched iTrip device takes a step closer to Brecht's wireless Apparatus of Communication by allowing you to clamp a tiny FM transmitter to the top of your pod. The iTrip then enables you to play your digital files through any FM radio. The perfectly styled pill-like trip-lozenge enables the previously private, internalised trip to extend beyond the wires of your headphones and out into the aether. The pod becomes a broadcasting unit engaging with what the International Necronautical Society term 'the mediasphere'. 23

Tom McCathy's INS "Manifesto" 24 states that:

"That we shall take it upon us, as our task, to bring death out into the world. We will chart all its forms and media... We shall attempt to tap into its frequencies - by radio, the Internet and all sites where its processes and avatars are active... Death moves in our apartments, through our television screens, the wires and plumbing in our walls, our dreams. Our very bodies are no more than vehicles carrying us ineluctably towards death. We are all necronauts, always, already."

In April 2004 the INS were granted a temporary London-wide FM broadcast license. A Transmission Room was installed at the ICA, and the project explored reception, transcription, transformation and transmission: hearing and calling. The INS's pursuit of 'death as a type of space which [they] seek to eventually inhabit' is explained in the press release for "The Second First Committee Hearings: Transmission, Death, Technology" - a performance-event at Cubitt:

"We've been looking at the lines of code transmitted over the wireless by the poet Cegeste just after he was killed in a road accident. The messages are picked up by Orphee on his car radio, in the dead zone between stations. Now, Orphee is the most celebrated writer in the world, but he knows that just one line of Cegeste's blows his work out of the water: 'Jupiter rend sage ceux qu'il veut perdre. Une fois. Je repete: Jupiter rend sage ceux qu'il veut perdre. Deux fois. Je repete ...' The broadcasts are modelled on British agents' or Resistance transmissions from occupied France. Obviously, that's an important reference for Cocteau in the fifties." 25

David Toop also tunes into the Cocteau film and the lure of the voice from the underworld recounting disconnected lines of enigmatic poetry. The first line he notes in the film is "Silence is twice as fast backwards... three times." 26 John Cage, prior to composing 4'33" had apparently discovered the non-existence of silence by listening to his own nervous system. With our personally germinated pod of memory seeds, in fragmented episodic trips each sprouting mutating branches of memories we charter a kind of dead space, a past space of disconnected people, places, images - a kind of limbo, traversing the acoustic netherworld.

Brecht's prophetic clarion-call to the radio industry may not have only provided a wire-frame for the Internet. What happens if we short-circuit the iTalk and iTrip? Could the white ear-budded listeners be organised into suppliers? Thousands of personally-curated sonic-plateaus self-talking across the dead space, random wireless agents ambulating the aether simultaneously transmitting and receiving dislocated field-recordings. The iTripper becomes an audio-blogger, a digital Harry Smith 27 , travelling, listening, collecting, archiving, the journey constantly sountracked by the electrostatic omnipresent ohm-hum of the digital universe.

Pete Townshend quoted on the colophon page of Performing Rites (Frith 1998, colophon)

Julia's Bureau was a room set-up by W T Steed in his house in Wimbledon for spiritualist meetings. After the death of a young American journalist Julia Ames Steed established a quarterly review of psychic matters, titled 'Borderland', one of the principle features of the publication was the posthumous 'Letters from Julia' later published as a book of automatic communications. Steed set-up the Bureau at Julia's insistence and it remained open for 4 years. Steed's daughter claims that her Father's voice made contact with the Bureau following his death onboard The Titanic in 1912.

Koestenbaum quoted in (Frith 1998, p.237)

Roberts asserts that brands have run out of juice and products now need the power to create long-term emotional connections with consumers in order to take the next step up - to Lovemarks. (Roberts 2004)

(Conaway 2004)

Sailor speaking to Lula in 'Wild At Heart' (Lynch 1990)

(Eschun 1998, p.171)

macslash.org/article.pl?sid=04/04/02/1920209

A large variable number used in the programming of a PRNG

From the sleevenotes to 'The Sinking of the Titanic' (Gavin Bryars 1998)

(Freud 1961, p.79-80)

(Reynolds 1990, p.126)

(Toop 1995, p.270)

(Mulholland 2002, p.274)

Lilly quoted in Escape Attempts (Cohen and Taylor 1992, p.173)

Needs a footnote

(Stephens and Graham 2000, pp. 181-183)

(Hicks 2004, p.135)

(Connor 2000, p. 368)

(Frith 1998, p.203)

(Goffman 1959, pp.77-78)

(Dika 2003, p.197)

A term used by Tom McCarthy, General Secretary of the International Necronautical Society in relation to Calling All Agents: INS Broadcasting Unit at the ICA, April 2004. Agents preparing a series of radio broadcasts monitored transcribed incoming signals which were subjected to various procedures resulting in scripts for re-broadcast.

necronauts.org/manifesto1.htm

McCarthy speaking at the Aconvention, Liverpool Biennial 2002. (McCarthy 2002).

(David Toop. 1995, p.140)

'Anthology of American Folk Music' edited by Harry Smith and released in 1952. Re-released in 1997 by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings